Is Driver San Francisco actually hardcore anti-copaganda?

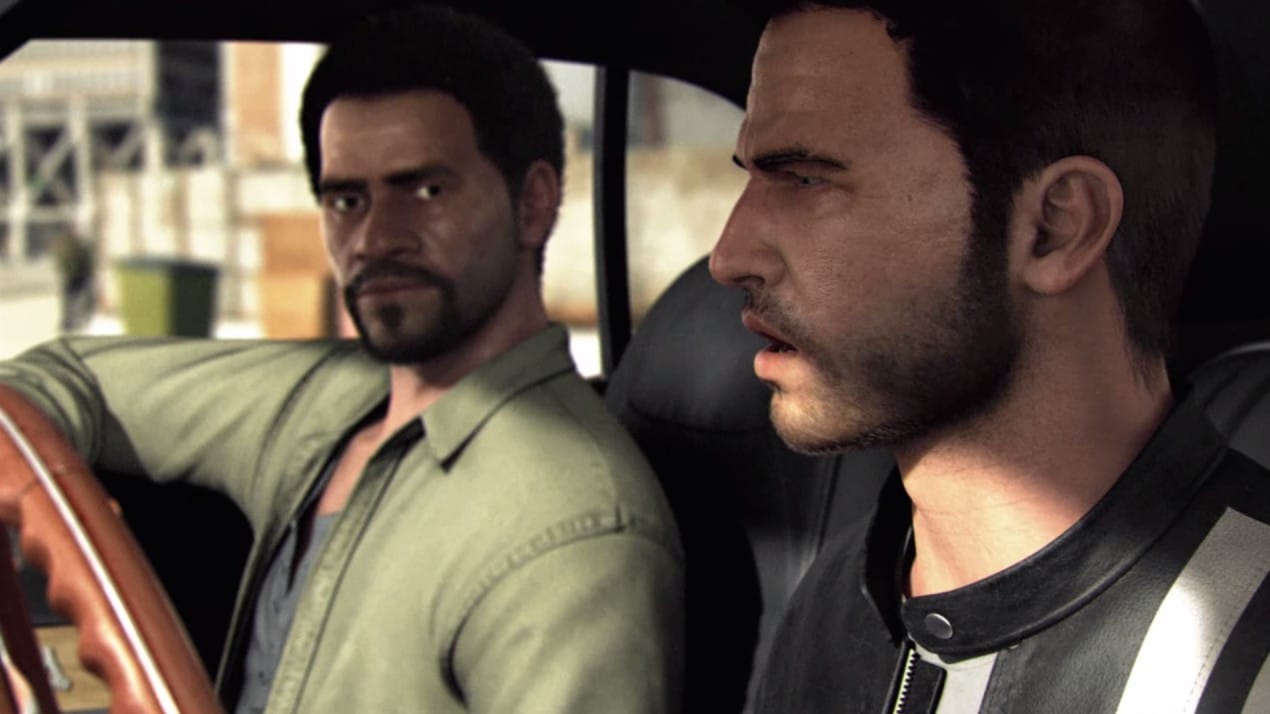

Tanner is an abusive, power-hungry, dangerous man with the backing of the US state. What a hero.

Copaganda (a portmanteau of cop and propaganda) is propaganda efforts to shape public opinion about police or counter criticism of police and anti-police sentiment.

The above definition is from Wikipedia, rather than a dictionary, because it isn't in the dictionary. Not yet, at least. It's one of those phrases that has an immediate mental mouth feel; a word that fills a gap in vocabulary and understanding that was always there. We forever kind of knew that certain media and marketing was designed to implicitly prop up the authority of the police, it just didn't have a name.

Copaganda is concerted effort to paint the police in a positive light; not just offering an opinion, but actively influencing how an audience feels about state-controlled authorities, in general and specific.

Defining anti-copaganda is a little more difficult. The concept is distinct from content that is simply anti-cop—stories and campaigns concerned with casting police in a negative light, or presenting them as villains. Anti-copaganda is a step further, painting police in unflattering (and, from the creator's perspective, realistic) ways that utilise the bombastic, hyper-real and persuasive language of propaganda. It's perhaps easier to think of anti-propaganda as satirical persuasion; using the tools of the other side to subvert the message, rather than offering straightforward opposition.

Driver San Francisco feels like a piece of anti-copaganda, but is it intentional?

Unlike other games in the Driver series—most of which followed the stylish but functionally realistic adventures undercover cop Tanner as he drove around various cities stopping crimes—San Francisco takes a wild and unexpected swerve into the world of magical realism. Tanner is hit by an armoured car at the start of the game and falls into a coma. From his hospital bed, he imagines his fight against infamous super-criminal Jericho continues, and he gains magic powers.

From inside this dream world, which Tanner sees as real, the player can project their soul into the bodies of other drivers on the road, effectively possessing them (and their car) for as long as he wants. Tanner calls this a 'shift'. His mind magic also lets him ram other vehicles by aiming the car at them, and imbues every car with a psychokinetic nitrous oxide boost.

There's no way to properly convey how insane this mechanic is inside a perfectly average crime-fighting driving game. Even in 2024, 13 years after the game's release, it seems like a design choice informed by mischievous fairies.

Driver San Francisco's shift mechanics are power fantasy, and not really that dissimilar from something like the abilities of Insomniac's Spider-Man or any given Assassin's Creed protagonist. But the narrative expression connected to these powers is wonderfully deranged.

Tanner immediately begins acting like a kid in a candy store, except the kid is a United States police officer, and the candy is the brains, bones, blood and barely insured property of innocent civilians. He smugly terrifies criminals by wearing their friends' faces as a mask; he tortures people by speeding down the wrong side of the road and ramping their car off the side of a bridge as they scream in fear; he creates fatal head-on collisions because it's good TV. Tanner spreads chaos through the city, giggling and foaming at the mouth while people suffer under the tyranny of his digital ghost. San Francisco is the most awful kind of playground for a god gone mad.

This all happens in a dream world, as the sort of cop out video games love to use when absolving players of violent and antisocial behaviour. Sure. Gamers are disgusting.

Driver San Francisco's escapist fantasy becomes more and more troubling when you remember the most important fact about Tanner (aside from him being in a coma): he's a cop. That means a cop is having all these thoughts, a police officer is gleefully taking up vehicular arms against defenseless civilians and undermining the fabric of society. From Tanner's perspective, this isn't a chance for him to let loose and experiment in a world without consequences, this is exactly what he'd like to do. If he had supernatural powers that robbed people of their autonomy it would be awesome, actually.

People are nominally horrified at the way Tanner acts and the chaos he brings, but it doesn't lead anywhere, and it gets Results™. Tanner's partner isn't happy about the weird behaviour, even though he continues to go along with it; the citizens scream and run, but seem generally happy that criminals are being punished. Strange, supernaturally-energised billboards speak directly to Tanner, standing as a physical representation of Tanner's belief that the city's population—the city itself—consents to his actions. "Do it," urges one sign.

The game is a fantasy in the sense of 'What if I had cool powers?' but also an imagining of a perfect world that has no problem with absolute power controlling absolutely. If it keeps people safe, it's good. The promise of an end justifies the means.

It might sound familiar to anyone with a less than favorable view of the police and their role in the modern world. A society with clear laws, except for those in power, who can break them if they deem it necessary. Carte blanche for the authorities to hurt anyone, provided they justify it with some greater good. State forces (or, in this case, magic forces) not beholden to consequences of any kind, and with the ability to control everyone's actions. Tanner even shares a common frustration shared with real-life law enforcement when it comes to serious crime: if I were just allowed to solve this my way, without anyone standing in my way, this wouldn't be a problem. Just give me a gun—or a car—and it'll all be over soon. You're welcome.

I'd be less inclined to offer this darkest possible read of Tanner if he wasn't so very excited to be a horrible person. The glee with which he executes multiple civilians in car crashes suggests he barely sees the residents of San Francisco as human. They're just little dolls in his rollicking adventure to be the best cop in the world. The grim enthusiasm on display can't help but remind me of satirical works like Starship Troopers, where the obvious is similarly never explicitly stated but always visible. The main characters' perspectives make them monsters.

"Something given has no value. When you vote, you are exercising political authority, your using force. And force my friends is violence. The supreme authority from which all other authorities are derived."

Driver San Francisco has its main character imagine a perfect world, and he creates one in which he has total power over its population. Not to bring it to something better, but to make it run according to his designs, and to help him achieve his goals. No matter how small they might seem when compared to the countless lives taken along the way.

Did Ubisoft Reflections mean for this to happen? You could argue they didn't, that they just made a fun car game where you can teleport between vehicles. But the intensity of Tanner's characterisation as a man out of control by our standards, the inclusion of so many opportunities to destroy the lives of strangers for little to no reward; it seems impossible. There's a void left by Tanner's lack of empathy that seems to beg for the player to fill it. Like many other examples of satire, by its absurd exaggerations it asks us to find it absurd, and then think through the implications. Driver San Francisco wants us to question the mentality and role of the police force without ever explicitly villainising it.

The anti-propaganda is teaching lessons rather than building myths. Tanner is our hero; and, given his actions, that should make you very uncomfortable.

It's tricky to ever really confirm satire, particularly in video games. You're always complicit in the mechanics and activities by virtue of the medium's interactivity. The experience is almost always enjoyable by design; fun is mandatory in the Fun Factory, especially for the people making games, no matter what messages or themes they might be attempting to communicate.

I'm a big fan of allowing creators the benefit of the doubt, though. If it hurts like a duck, wears jackboots like a duck, upholds the status quo of the rich and powerful like a duck. So there's an inclination to take Reflections at their word here. Those words seem to be 'cops are barely-restrained human weapons, who have been molded by a corrupt system to enjoy abusing the power they hold over a society they claim to protect.'

Oh, and 'car go fast.'