What video game's easy mode makes me feel the worst about myself?

Games used to put a lot of effort into making players feel bad and then they stopped. Thankfully, gamers took over.

How do you frame the value of a particular experience? Video game difficulty is an often raised point of discussion among both Gamers and People Who Play Games, periodically emerging from the floor like a trapdoor spider to kidnap the unsuspecting and suffocate them in its discourse cave.

Accessibility settings, the existence of Dark Souls, whether or not something is appropriately hardcore.

In times gone by, games themselves fell mostly on the gatekeeping end of the spectrum. Several major titles were designed to further the opinion that games have difficulty levels, and if you choose the lowest level then you are a worthless, trash-eating scumbag with brain damage who should be tossed in the ocean. A more modern approach is to generally avoid insulting your audience and belittling the disabled, with lower difficulties often rebranded as 'story' or 'relaxed', putting the focus on the effect the mode has on the experience.

Wanted: Dead was released in 2023, and includes a mildly insulting easy mode. This is a curious anachronism, but the whole game is like that, littered with design choices that feel 15-20 years old. I mean this as a compliment (I think) as it gives the whole experience an air of archaeology, the sensation that you've dug up a relic of the past studded with ideas forgotten too soon.

The easy setting is called "Neko-chan mode" and, in addition to making the game less punishing in a variety of ways, it puts a pair of cat ears on the main character. You know, it's like you're a cute catgirl now. Admittedly this isn't the most intense example of shame-branding—some people would pay real money and commit real crimes to be a catgirl—but it is a deliberate branding nonetheless. You picked easy and you should not forget. All who view your game footage shall look upon the widdle uwu baby ears and despair. This lampshades a trend across these modes to make sure that the player isn't really allowed to continue playing the game without facing their choice. Video game will remember this.

Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, in a similar vein, has a chicken hat. Two chicken hats, actually, each of them more chicken than the last. I would rate these as a little higher on the shame scale, because a cat is just a cute little cutie, and a chicken is the international symbol for a dirty coward. Once you fail a mission a decent number of times, the game will stone-facedly offer you the silly hat, which makes you mostly invisible to enemies. You aren't forced to wear it, however, so it can just sit in your inventory as a private and personal reminder of your failures.

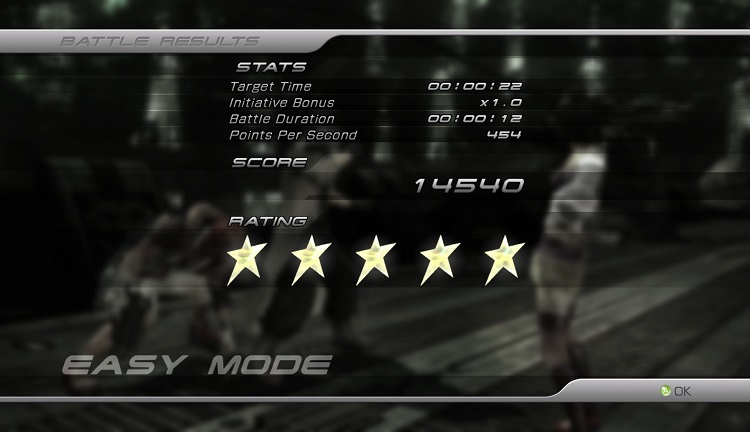

Final Fantasy XIII (or FINAL FANTASY XIII, according to my steam account) has an easy mode (or EASY MODE, according to the game's UI). It's not a terribly common sight for JRPGs in general, being a genre that answers the question of difficulty by simply allowing you to break the game by putting in enough time and effort. I was excited to see the option in FFXIII; while I enjoy the strategic challenge of a sprawling, turn-based RPG, I am also old and busy, and admittedly mostly there for the stories about evil sorceresses and steampunk towers.

Except the game then plasters every victory screen in every battle with EASY MODE. The battle results screen, which already rudely grades your performance out of five stars based on inscrutable algorithms, screams at you a thousand times over the course of your adventure.

You picked easy mode, remember. None of your achievements are worthwhile. Other people played this game on normal mode, you goddamn weirdo.

The need to keep the player aware of their difficulty choices feels somewhat indignant in these cases. It gives the impression that there is a right way to play, and you're doing it wrong by picking easy. Destroying the intended experience of Blorkins 5: Get Blorked by turning on auto-aim. It calls to mind a recent minor ruffling of film director feathers by recent moves to watch more films at home—as if most people's primary experience of movies isn't already renting or streaming something on Friday evening to put on while you do the dishes.

Art can be positioned as entirely subjective, completely objective, or anything in-between. Books have been written about this, TEDs have been talked. But games as guided experience have this alternative option where the developer controls how the fingers touch the art, how long the eyes look and what they do while looking. The Zombification of the Author; he's in your house, telling you not to play on easy.

All that to say that Final Fantasy XIII's easy mode does make me feel kind of bad about myself, and that's annoying.

Some games that used this sort of schoolyard bullying approach to player experience at least had the decency to confine it to the main menu, making up for that concession by treating you more explicitly like a piece of shit. Wolfenstein 3D is perhaps the most well-known example, historically, with a difficulty screen that looks like this:

These difficulty options are framed not as measurements of how challenging the game will be, or what effect they have on the gameplay, but as feelings. Vibes. Importantly, they are the feelings you are promised if you're good at these difficulty settings; overcoming the increased challenge of choice three and four will feel amazing, unless you're bad at the game, in which case you get to double your shame by turning the cool meter down. Or you can be a baby who poops his baby gamer pants and does baby things.

While the initial intent is absolutely to make me feel bad about myself, the general absurdity of this one puts it low on the list. I can't take it seriously enough to be sad. Thankfully we've moved on since 1992.

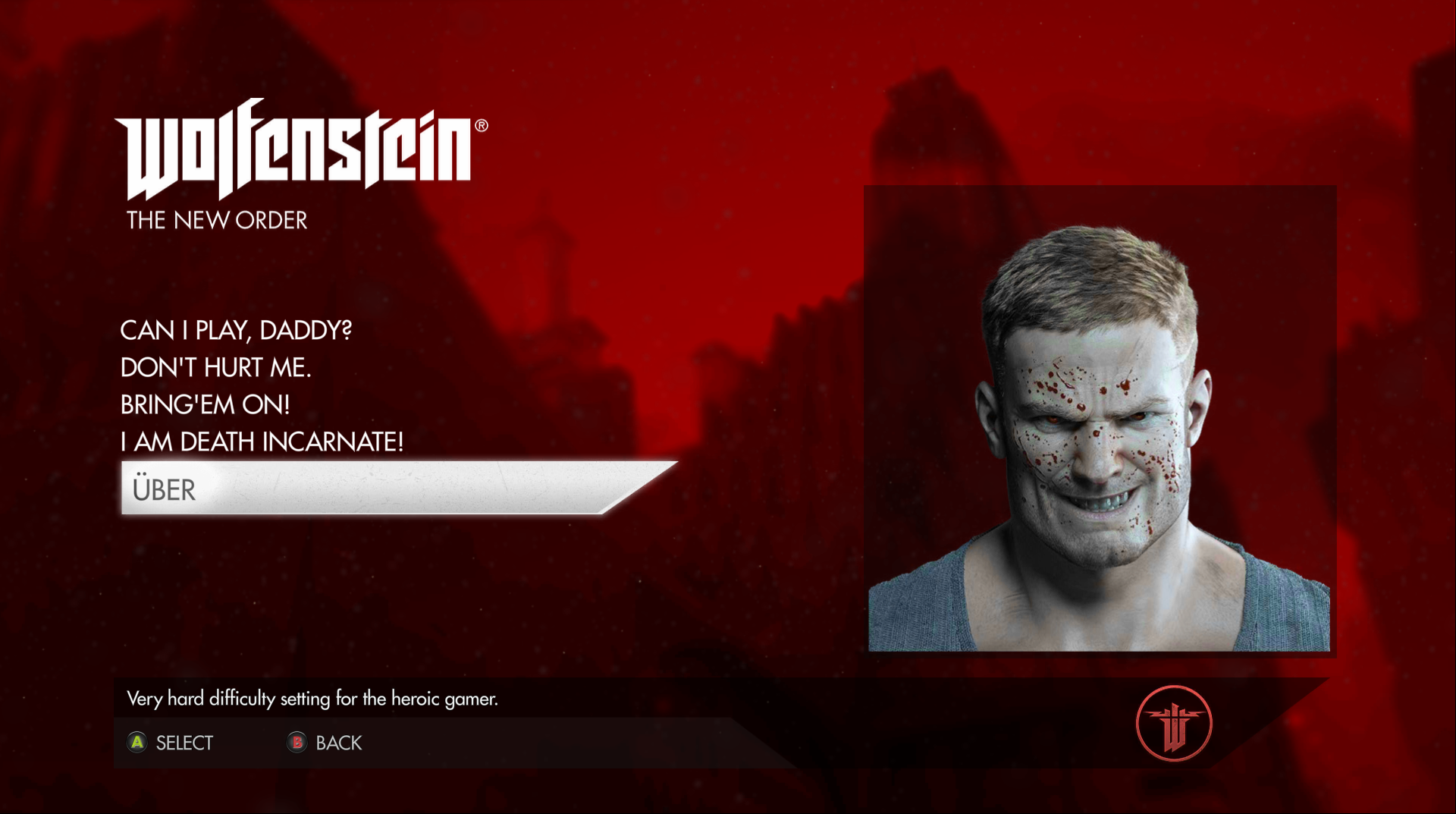

No, wait, I'm being told that 2014's Wolfenstein: The New Order replicates these exactly. Divorced of context and tone by two decades of social progress, you can still be called a baby loser. Shortly after this selection, the game will force-feed you the unfiltered horrors of its version of World War II, invoke the holocaust, make the player decide which of their friends will be brutally murdered in front of them, and spend a significant amount of screen time detailing the existential nightmare of living in a medical facility for years as a near comatose victim of a brain injury.

He's wearing a baby hat though! That's pretty funny.

The New Order also includes an extra-hard, extra-hardcore difficulty level called Über. Part of the charm of Wolfenstein's hero William "B.J." Blazkowicz is the poetic upending of Nazi ideals about their own perfection, as their plans and skulls are exploded by a superhuman from the side of the fight they want to exterminate. But the Nazis had a particular fondness for the term Übermensch, and it feels... uh... it feels a bit weird to be championing that as the peak of Gamer Ability. A little weird. That's all I'm saying.

You can feel a friction between two ideas. Difficulty is mechanical, systemic, it's a pure gameplay decision between two similar yet unique experiences. Difficulty is a message, a line in the sand, a big neon sign telling players how much to value themselves. Feel bad, it screams at the easy player.

Ironically, this flip-flopping between mechanics and narrative is why none of the old-fashioned insult screens a la Wolfenstein work that well. Telling me I'm a baby for playing with stronger guns or weaker enemy skin suits, hurling toxic masculinity in my face, trying to trigger my gamer urges, it's simultaneously trying very hard and producing something comically meaningless. Like a small child saying you're a big poopy head with a dumb face.

I'm an adult. If you really want to hurt me, just do what my mum always did: tell me you're a little disappointed and then offer some brave-faced encouragement.

I knew the answer from the beginning. It's always been the same answer. The original Devil May Cry, for the PlayStation 2, is the soul-crushing singularity. All games of Devil May Cry begin on normal difficulty, but if you die several times, or use a major health item early in the game, it prompts you to try something called Easy Automatic mode. This mode significantly reduces the difficulty of the game in many key ways, but none of them really matter. That prompt, that helpful little moment where the game steps in to suggest you might be in over your head, is the most offended I have ever been by a video game.

"Hey champ, you doin' okay? Looks like you're struggling with that mean old game a little bit. Need some help? You need a hug? Come here buddy, it's okay, gaming isn't for everyone."

Capcom's acknowledgement of my dumb baby fingers hurt like heck, but luckily I got over it, and I don't think about it frequently. Stop saying that I think about it a lot. Stop telling people that. Don't print in the newspaper that I'm thinking about it.

Devil May Cry's method does effectively frame the issue, however, overlooking the use of terms like 'easy' and 'normal' for a moment. Difficulty isn't real; at least, not in the sense that a video game wants to quantify. You and I can find a game challenging or simple for wildly different reasons, and neither of those opinions are provably incorrect. So the wild revelation about that dichotomy between mechanics and narrative that I mentioned earlier? It's the mechanics that aren't really important to discussions about challenge.

The challenging experience matters because it's been built to matter, mechanics only exist to make the challenge happen. They're a tool for evoking feelings.

Dark Souls isn't an infamously difficult experience because the developers put as much 'hard game' sauce in as possible, it resonates as a challenge because the considered experience of fighting for every win and struggling to reach every new shortcut is presented as the intended experience. Dark Souls isn't even difficult in the traditional sense, it merely encourages players to closely examine their path through the game. Dead Cells doesn't kill you over and over to prove how hardcore it can be, they intentionally set that challenge in the context of a world that runs on decaying cycles and repetition.

Old-fashioned, antagonistic difficulty settings mostly went away because of a greater focus on the idea that allowing everyone to play was usually a better idea than being an asshole. But they were also a shallow way to engage with an experience, and usually ran counter (or at least perpendicular) to the game's own messages.

Honestly, the cat ears look good on me.